The Science of a Perfect Soft-Boiled Egg

If you google “how to make a soft-boiled egg”, you will probably come away with the impression it’s all about timing. Some recipe authors even urge you to use a timer. The first clue that doesn’t work is they all tell you different cooking times. Is it something in the water?

In a way, yes. Cooking an egg is transferring heat to the egg, via water. Before we propose a solution for making a soft-boiled egg, let’s first define the problem: what is a perfect soft-boiled egg?

This is my definition: it should have a soft, gel-like egg white with mostly runny egg yolk. The white should be solid but not rubbery. The yolk should be runny but not watery. Also, we will not sacrifice food safety for texture. Even though the yolk is still runny, there should be practically no risk of salmonella.

The biology and chemistry of eggs

Egg yolk is special. Normally, stuff becomes food because humans decide to eat them. Egg yolk is designed to be food by nature. It’s food for the chicken embryo. Egg yolk accounts for 1/3 of the egg’s weight, but carries three-quarters of the calories. It’s rich in fat and protein. When the proteins are heated, they denature and then coagulate, forming an interconnected network that solidifies the yolk.

The yolk sets somewhere between 60⁰C and 65⁰C. If the temperature stays above 65⁰C for long, the yolk will turn solid. On the other hand, if the yolk’s temperature is not high enough for long enough, salmonella in the yolk will survive. To be safe and quick, I would hold the yolk at 63⁰C for 5 minutes. (We talked about the thermal death curve in secrets to happy cooking). It’s not straightforward to measure the temperature of the yolk, and even harder to control it precisely. We will tackle this problem later in this article.

Meanwhile, 90% of the egg white is water. There are trace minerals and a little bit of glucose. It’s too little for the egg to taste sweet, but it enables the Maillard reactions that turn the egg white in the Chinese thousand-year eggs (皮蛋)brown.

The rest of the egg white consists mostly of proteins. As designed by nature, they are not food, but protection for the embryo. One protein inhibits viruses. Another kills bacteria. Multiple proteins blocks digesting enzymes. Contrary to the teaching of a master in an old Kungfu movie (where all boys get their nutritional advice, naturally), eating raw eggs actually causes lab animals to lose weight. It takes high temperature to deactivate the proteins’ biological functions and turns them into nutrients.

Different proteins in egg white set at different temperatures. The most abundant protein in egg white, ovalbumin, doesn’t coagulate until about 80⁰C. It seems contradictory to our experiences, but that’s why the Japanese Onsen-tamago(温泉蛋)gets its semi-solid yolk and watery white. In the hot spring, the egg is held in a water bath at a temperature where the yolk starts to set but some of the proteins in the white have not coagulated.

We have only scratched the surface of the biology and chemistry of eggs. But we know what we want from the perspective of cooking: in addition to the right texture, we want the proteins in egg white to expereince high enough temperature to denature so they don’t fight our digestive enzymes; and we want the egg yolk to be held within a narrow range of temperatures. How do we achieve that with heat?

The science of heat

Heat is thermal energy in transit. It’s not stationary thermal energy, nor is it a measure of the energy (that would be temperature). Heat is a dynamic concept. It’s probably easier to always think of heat transfer, instead of just heat.

The three modes of heat transfer are conduction, convection, and radiation. Heat transfers by conduction in a stationary medium. A common misunderstanding is that convection is how heat transfers in a fluid. Actually, convection means when heat transfer occurs between a surface and a moving fluid. Finally, if there is no medium between the heat source and the object receiving the heat, like between the sun and the earth, heat transfers by radiation. Let’s see how to analyze the different modes of heat transfer.

Conduction

Figure 1 shows our cooking setup: the pan conducts the heat from the burner to the water, which covers the egg. A common question from cooks is: what is the best pan? From the perspective of heat, one desired property of a good pan is: It holds its temperature when cold food is added. A substance’s capacity to hold heat is called its specific heat capacity. It measures how much thermal energy it needs to gain or lose for its temperature to rise or fall by 1 degree per unit mass. Cast iron is commonly thought of as retaining heat well, but it actually doesn’t have a particularly high heat capacity (460J/kg.K). It’s lower than that of stainless steel (490J/kg.K) and much lower than that of Aluminum (910J/kg.K). But what cast iron lacks in heat capacity, it makes up for in density. So in the same volume, cast iron has more mass and retains more thermal energy than Aluminum.

The other desired property of a good pan is that it conducts heat quickly. Conduction follows the Fourier Law. The simplified form of the Fourier Law in one dimension is:

The heat flux q”(W/m²) is the heat transfer rate in the x-direction per unit area. The thermal conductivity k (W/m.K) is a characteristic of the pan material. The derivative part represents how fast temperature changes over the depth of the pan. The Fourier Law shows that:

- Heat only flows in the direction of decreasing temperature.

- Heat flows faster if the rate of change for temperature is greater.

- Heat flow doesn’t stop until everything is at the same temperature.

- Specific to conduction: heat transfer rate only depends on the conducting material and the temperatures at the boundaries, and nothing else. If you can not change either, you can not change the amount of heat flux by conduction.

But to answer our question of how fast heat transfers, the Fourier Law is missing an important variable: time. Cast iron’s thermal conductivity (55W/m.K) is higher than that of stainless steel (~40W/m.K), but we all know that the cast iron pan heats up very slowly. The reason is that some of the heat coming in the hot side doesn’t go out the cold side. It goes to heat up the medium. Per the first law of thermal dynamics (conservation of energy), we can write out the energy balance function:

Eₛₜ is the energy stored in the material over time. It’s decided by the density, specific heat capacity, volume, and how much temperature changes over time. Here we introduced the time variable because all the net energy inflow changes the stored energy, hence the temperature, over time. Combining the energy balance function, the Fourier law, and a little calculus, we will arrive at the heat equation:

Don’t worry about the scary differentials. The left side of the heat equation is about temperature changes over space. The right side of the heat equation is about temperature changes over time. The physical significance of this equation is: the temperature distribution at the beginning decides the temperature distribution over time. The spatial distribution and the temporal distribution are related by α= k/ρcₚ. K is the heat conductivity. ρ is the density. cₚ is the specific heat capacity. α (mm²/s) is called the thermal diffusivity, which tells us how fast a burst of heat spreads throughout the material. Material with high thermal diffusivity is more responsive to the change of heat input, giving the chef better control. The champion among common pan materials for thermal diffusivity is copper: 114.8mm²/s.

The solution to the heat equation tells us how temperature changes over time. Fourier’s analytical theory of heat was initially rejected by prominent scientists like Lagrange and Laplace. He was only published after he, searching for the solution to the heat equation, discovered the Fourier transform, which is incidentally also the mathematical foundation of wireless communication.

The analytical solution for the heat equation is usually quite complicated. However, it can be shown that, with some assumptions that are valid in normal cooking situations, heat diffusion time is proportional to the square of the depth. It’s a good rule of thumb for estimating cooking time.

Convection

At the top surface of the pan, heat transfers to water by convection. When particles of free-flowing fluid make contact with a surface, they are slowed down. In most cases, it’s valid to assume their speed is 0 at the surface. These particles then slow down the particles in the next layer of fluid. The particles in the next layer in turn slow down the particles on the layer above it, and so on and so forth. Eventually, this retardation effect becomes negligible. The region where the fluid speed gradually changes from 0 to the speed of the free-flowing fluid is the velocity boundary layer.

Similarly, the fluid particles that come into contact with the surface achieve thermal equilibrium with the surface. They heat up the particles in the next layer and the next layer. Eventually, a temperature gradient develops in the thermal boundary layer.

Assume the temperature at the top surface of the pan is Tₛ, and the temperature of water far from the surface T∞. Newton’s law of cooling states that:

q is the heat flux. h is the convective heat transfer coefficient. The heat transfer coefficient is affected by many interdependent variables. The problem of convection is to determine the transfer coefficients.

By the way, this type of equation is quite common in naturally phonomena: the rate of change of something is proportional to the difference between two states and a constant characteristic. We saw this in the Fourier law, the Ohm’s law, and we will see this in the Darcy’s law that explains how water flows through a bed of coffee ground.

For the cook, the bad news is that in reality, the flow of fluid near the surface is much more complicated than nicely separated layers. It’s therefore very hard to analyze the boundary layer in cooking liquids. I would say it’s probably not worth it to try. The good news is that, unlike the thermal conductive coefficient, the chef has some influence over the convective heat transfer coefficient without changing the ingredients. Here are some key insights from the study of convection that we can apply in the kitchen:

- The faster the fluid flows past the surface, and the more turbulent the flow, the larger the convective coefficient. That’s why blowing on hot food can cool them down.

- Because of the existence of a velocity gradient, there is bulk fluid motion perpendicular to the surface. This motion is a major contribution to convective heat transfer. In a very thick liquid, there is very little movement and the velocity boundary layer is not developed. Heat transfers by conduction, not convection. That’s why you need to keep stirring a thick tomato sauce to create forced convection. Otherwise, the bottom will burn while the top is still cold.

- Liquid has a much bigger convective coefficient than gas. A ratio of 100 to 1 is typical. Most other cookbooks will say here that’s why you can put your hand in a hot oven without getting burned. I will give you a more useful example: if you want to burn a lot of calories, do your exercise in the pool. The convective heat loss from staying in the pool for an hour is greater than the calories you can burn by running on the treadmill for an hour. Another example is that thawing in ice water is much faster than thawing in the fridge air, even though the former is at a lower temperature.

Radiation

We do not intentionally leverage thermal radiation in this setup to cook the egg. However, thermal radiation is everywhere. It’s coming from the walls around you, and the chair you are sitting on. It’s an important mode of heat transfer in ovens and on the grill. We will have an in-depth discussion of radiation in The Science of Toast.

Cooking the egg

On the outer surface of the eggshell, heat transfers by convection. On the other side of the egg shell, i.e, inside the egg, the heat mostly transfers by conduction. It’s something the cook can not get around no matter what is being cooked: you can try to control how heat gets to the surface of the food, but once it gets there, you lose control. Inside, the material and composition of the food completely determine the nature of heat transfer. The best you could hope for is good data about the temperature gradient inside.

Conventionally there are three ways to control the heat distribution inside the food. The first is to control the heat input to the food by controlling the duration and intensity of the burner heat output. The cook can turn the knob on the burner and decide when to turn it off completely. There are different oven and stove technologies, but at the end of the day, most home cooks only have rough control of the output power and timing. Clearly, multiple conditions for the equations that govern heat transfer are not under control, and what can be controlled is not controlled with precision.

The second way is to cut food up. Chefs often emphasize you need to cut food into equal sizes. The idea is if they are the same size, they will be cooked to the same extent. Stir fry recipes often call for thinly sliced food. In stir fry, ingredients touch the hot surface only briefly. To make sure everything is cooked through, it’s important to increase the ratio of surface area and volume. With less depth for the heat to penetrate, it’s easier for the chef to judge the temperature inside the food by looking at the surface. I suspect that’s why expensive Wagyu beef always seems to be cut into small pieces when grilled (but then I realized, a more compelling reason may be: if you are paying so much for it, you shouldn’t have to cut you own food).

Both of those methods are imprecise and highly dependent on the skills and experiences of the cook. The fundamental problem is a mismatch of the input (heat) and the desired outcome (temperature).

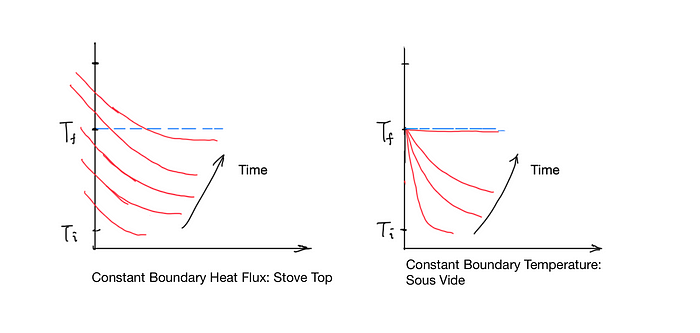

Figure 6 shows the temperature distribution inside food over different boundary conditions. Tᵢ is the initial temperature throughout the food. T𝒻 is the desired final temperature. A typical stove can be modeled as a heat source providing constant heat flux. A constant heat flux means a constant temperature gradient. Over time, the surface temperature of the food rises, and an undesirable temperature gradient inside the food develops. As you can see from the left side of figure 6, part of the food is overcooked and part of the food is undercooked. The only way to eliminate the undercooked portion is to turn off the heat just in time and let the residue heat to finish cooking. Without quantitative data on the curve of temperature vs depth and how it changes over time, the chef can only rely on experience. There is only a very small window to get it right, and part of the food is inevitably overcooked.

However, if we change the boundary condition and keep the surface temperature constant, eventually all of the food will achieve thermal equilibrium at exactly the right temperature. You don’t need to worry about how the temperature gradient inside the food is, and you don’t need to worry about carry-over cooking, because there is none.

The technique to achieve this is Sous Vide cooking. In essence, it’s cooking food in a constant temperature water bath. Not only does it make it possible to achieve uniform temperature inside food, it also gives you much more precise control of the temperature. If you have always poached salmon in stock, you will never know the difference a couple of degrees (from 49⁰C to 51⁰C) makes. Sous vide also creates very pure tastes. Carrots cooked sous vide taste different from roast carrots because it doesn’t have the flavor developed by the Maillard Reactions under high temperature.

Sous vide cooking is a vast topic that deserves its own dedicated article. I will close this discussion of Sous Vide by saying that, though it’s not the solution to all your cooking problems, due to its unique advantage from the perspective of heat transfer, it should be an important tool in any chef’s toolbox.

As mentioned earlier, if we want the egg yolk to be runny and safe to eat, we need to make sure it reaches around 63⁰C for 5 minutes. The only way to ensure that is to cook the egg in a 63⁰C water bath for a sufficiently long time. As mentioned above, this temperature does not set the white. We still need to heat the white to a higher temperature. In Modernist Cuisine, the suggestion is to dip the egg in boiling water after sous vide.

We have one last problem: peeling the egg shells. The most useful advice I can give you is: stop looking for a magical way to peel the egg shells cleanly. There is none. The only kind of eggs with easy-to-peel shells are overcooked eggs and old eggs. My solution, especially for perfectly cooked soft-boiled eggs with delicate whites and runny yolks, is not to peel them at all. Instead, use an egg topper. It takes some practice, but anyone can master it.

Building a better egg cooker

Every egg is different. Any time-based cooking process will not produce consistent results. The only way to do that is a temperature-based method.

Eggs should be started in room temperature water bath. The water bath is heated to the desired temperature (63⁰C for a soft-boiled egg). The gradual heating process let the air in the air pocket inside the egg slowly leak out. Otherwise, the air pocket might expand too fast and crack the egg shell. How long should the water bath stays at 63⁰C can be estimated by the weight of the egg. One possible solution is to estimate the weight of the egg(s) by comparing the density of the water+egg with pure water. This only matters if the user wants the egg ASAP. Otherwise, you can keep the water bath at the desired temperature for much longer. Of course, the cooking start time should be programmable.

To increase the convective heat coefficient, the water flow should be designed such that the water flows faster near the surface of the egg, and perhaps with controlled turbulence.

When the egg is done, water is drained from the water bath. heating elements in the walls will rise to a high temperature and direct intense radiating heat at the egg shells. This should both coagulate the egg white and burn/crack the eggshells for easy peeling.

Enjoyed this article? 🌟 Help spread the knowledge by forwarding it to a friend and don’t forget to follow me on Medium for upcoming posts. Your support is much appreciated — thank you!